January 9th marks the launch of Roster, a hot-off-the-press print portfolio co-published by Marginal Editions and 56 HENRY, accompanied by an exhibition of the editions produced in collaboration with the gallery program.

In gestation for over four years, Roster is a testament to the commitment of Brad Ewing, who emailed the gallery almost 5 years ago to see if they’d be game to wrangle their artists to work with him. Ewing is synonymous with his imprint Marginal Editions, a double entendre winking towards the unprinted part of a piece of paper, as well his dissident status in the print publishing universe: scrappy, clever, economical, provisional, inventive, and the practical result of the parasitic occupation of the off-hours in academic facilities and a long-established print shop near the plant district.

Roster is emblematic of the thriving creative capital that emerges from the most compromised conditions in New York City, a notion that is buttressed by the portfolio’s clamshell box, designed by Kate Shepherd and produced by Sarah Smith. The prints are symbolically hidden away behind a trompe l’oeil container meant to appear as the ubiquitous New York green-painted plywood construction site, cut with a diamond-shaped peephole, sealed up with chain and a padlock, and complete with a faux spray paint stripe.

It is no wonder that Ewing saw a kindred spirit in 56 Henry, a vital and viral gallery clawing its way through marginal spaces in Chinatown. The proprietor of this growing and askew empire is Ellie Rines, who is an alchemist of filling these constrained spaces with big crowds and unconstrained talent. In her previous space, 55 Gansevoort, then located in the meat-packing district, exhibitions were only viewable through the window or when someone left the door open. When visiting her galleries, have you had to negotiate with obstacles particular to the sidewalks of Chinatown? Moving past a sleeping person, or climbing over leaking bags of fish and vegetables? Once inside, have you collapsed on a pile of jackets or the folding futon in the gallery office (bigger than the front exhibition space, but not by much) to converse with the pile of shredded jeans and tights holding laptops that represent the gallery staff ? Have you gleaned a sick friend up in the bed above the gallery office in the loft Rines used to sleep in? During an opening, have you locked yourself in the gallery bathroom, as I have, when the doorknob fell off, but found yourself saved because the bathroom shower was filled with the gallery’s slipcased inventory and the tool kit? The drill battery was fully charged at least, so the door hardware could be removed and pliers handed though the hole to the crowd outside to liberate you. Did I mention that the shows are all really good? That the artists are all amazing?

These anecdotal observations are not merely fodder for the gallery legend, but an acute illustration of how to make a lot out of a little, while preserving the vibe of making into the made. For both Ellie’s roster and Ewing’s portfolio of their prints are inventive, urgent, and spirited. “Well built of the heart’s lumber,” Dave Hickey once wrote, but perhaps more apt in this case would be an updated “rough-hewn from the heart’s lumber."

In producing the thirteen prints, Ewing took great care to encourage each artist to exploit their natural attributes, and final decisions were made to accommodate the artist’s methodology. Notable examples include preserving Jo Messer’s spilling gestural lines (which increased the need to expand the size of the portfolio dimensions), and Cynthia Talmadge’s print containing clever score and fold elements that ensure the print fits inside the portfolio box. For Pierre Bellot’s print, Ewing wanted to preserve the incidental mark-making outside the print-image, which another publisher might seek to erase from the margin. These nods to the physicality of process are echoed in the embossed doorknocker earrings in LaKela Brown’s variable gold-plated print, as well as the excavated section of Ohad Meromi’s veneer print that allows for a flush mounted Chine collé element.

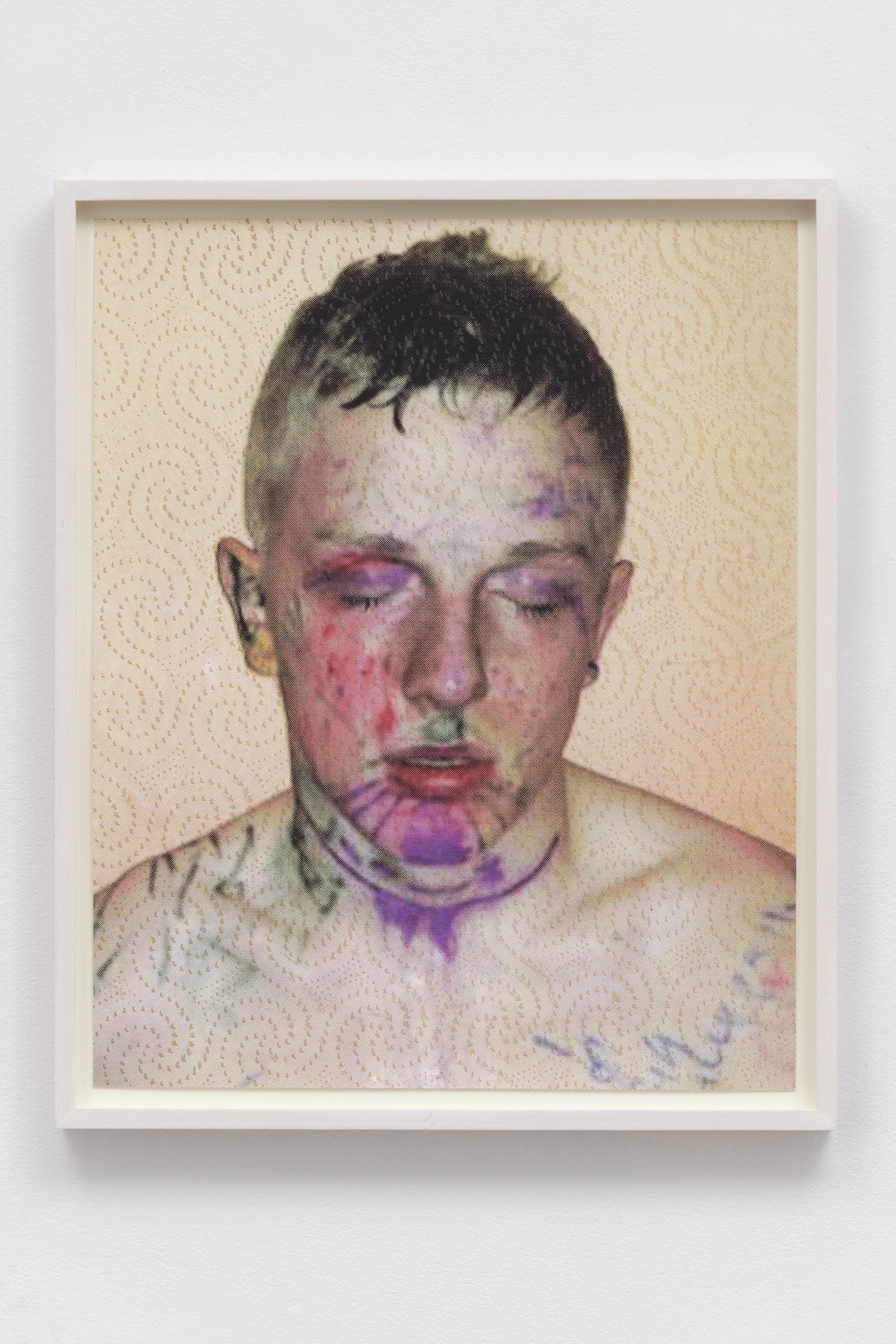

Ewing’s specialty (and the shop he works out of) is letterpress, but he incorporates silkscreen and other techniques to achieve interesting results. Another printer might use more orthodox methods, but Ewing pushes print techniques out of their comfort zone. Use of variable editioning and deliberate off-registration give prints more lively qualities, including the split fountain technique used on Richard Tinkler’s delicate screen-printed line-work, and the loose color registration the prints of Mika Horibuchi and Clayton Schiff, which enhance the feel of their drawing techniques. Ewing’s tendency to achieve vibrant effect from enhanced layering is evident in the prints of Al Freeman, Daid Puppypaws, and Nikita Gale, which convert source imagery into sublime colorfield experiences.

As much as Ewing likes pushing process, he can also be an egoless collaborator in search of the best result. For example, he misunderstood Christopher K. Ho when he made his printing plates, but they both embraced the inverted accident to produce something Ho ended up preferring. And for Kevin Reinhardt’s industrially screen-printed and laser-cut polycarbonate edition, Reinhardt handed Ewing the stack of nearly finished prints direct from the assembly line and asked him merely to use a circle gauge and a sharpie to circle the edition number.

There is probably a decent metaphor in that last description about the facilitators hidden behind the named and signed artworks that are disseminated into museum collections and on collectors’ walls, that will long outlive the places they were made or shown. For Rines and Ewing, it’s a legacy built out of a rough-hewn labor of love despite crumbling infrastructure, a mountain of production costs and monthly bills, and a ton of logistical challenges. Against all odds, they are making it happen.

- David Kennedy Cutler 12/24/24