Presumed Innocence, or Fifty Shades of Green: On the Work of Anna Weyant

by Jens Hoffmann

To make art always also means to insert oneself into a particular conversation with the past in order to assess what has already been done, by whom, and how, but also to engage in conversation with what is taking place at this particular moment. Anna Weyant takes this idea very much to heart in her first solo exhibition, Welcome to the Dollhouse, presented at 56 Henry in New York. Weyant was born in Calgary, currently lives in New York, and graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2017. Welcome to the Dollhouse brings together some concerns from her previous work—circling around questions of youth and adolescence—with the wicked reality of growing up. The title is a direct reference to Todd Solondz’s 1995 movie of the same name—a tragicomic coming-of-age story about a teenage girl, Dawn Wiener, whose schoolmates call her Wiener Dog. Dawn undergoes all sorts of humiliations and abuses while attempting to fit in, in large part because her manipulative and cruel little sister, Missy, sabotages all of Dawn’s efforts to join the crew of cool kids at her school.

Weyant’s artworks take cues from Dutch Golden Age paintings; the artist frequently mentions her adoration for Gerrit van Honthorst, Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hals, and Henrick Terbrugghen. Yet it is unclear if she fully embraces that tradition, even if she calls upon a lot of its tropes; indeed, she is just as knowledgeable when it comes to modern and contemporary art and popular culture. There is a lot of tongue-in-cheek humor about everything she does. Her paintings are playful, tragicomic, and haunting, and sit firmly in a lineage of contemporary artists like John Currin, Elizabeth Peyton, Rita Ackermann, and perhaps even Lisa Yuskavage.

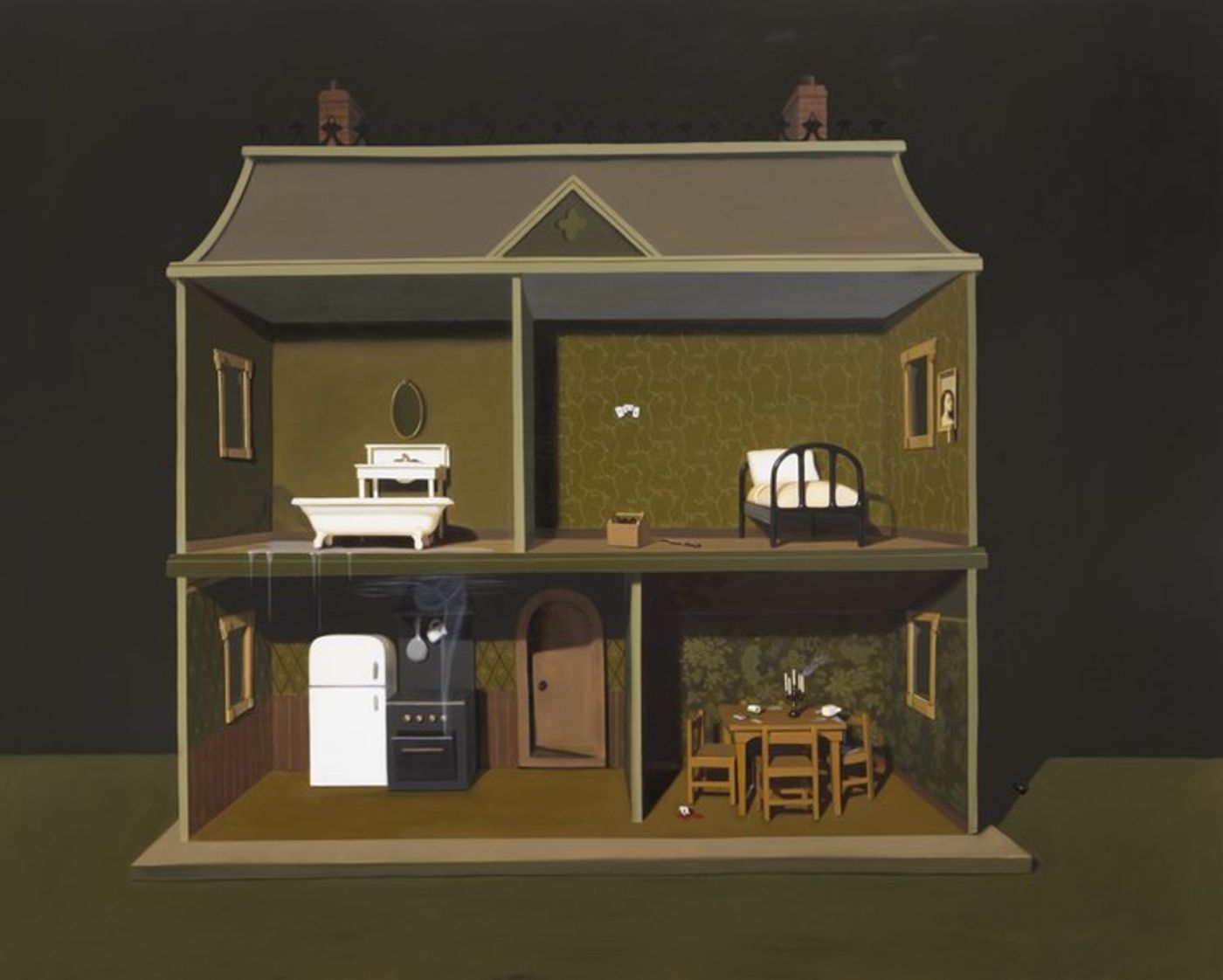

The show features a dozen paintings in total. Two are of a dollhouse, one showing its facade and the other an interior cutaway. The former is titled Let there be (some more) light, evoking René Magritte’s iconic Empire of Light series, and also of course the creation of the world in the Book of Genesis, an English translation of the Hebrew sentence יְהִי אוֹר (Let there be light) in the Torah, the first part of the Hebrew Bible. Anatomy of a Doll’s House, the interior view, might refer to Norwegian writer Henrik Ibsen’s 1879 drama A Doll’s House about the awakening of a middle-class society in Norway at the end of the eighteenth century—a society not unlike the one Weyant comes from. Perhaps tellingly, she uses the same phrasing as the British translation of Ibsen’s title, “A Doll’s House,” rather than “Dollhouse,” as is more commonly said in the United States. Anatomy of a Doll’s House presents us with a bathroom, a living room, a kitchen, and a bedroom, all empty, waiting for the play to start. It brings to mind the infamous empty houses of Huguette Clark, the twentieth-century heiress and philanthropist who lived in various hospitals and other institutions, leaving her several large mansions unoccupied. One likewise can’t escape thinking of Amy Bennett’s paintings of typical American middle- and upper-middle-class suburban exteriors. There might even be a bit of Laurie Simmons’s early photographs of domestic dollhouse scenes in Weyant’s paintings. Yet Weyant seems less interested in reflecting on the role of women in the Western nuclear family than in families’ hidden and un-discussed underbellies. Looking more closely at Let there be (some more) light, we notice that the house’s door has been opened by force: it is open and its knob is broken off. There is a shoe nearby, perhaps left by a Cinderella-like character.

The other ten paintings, hanging on the opposite wall, depict individual rooms of the house populated by a group of girls. We know that Weyant’s personal dollhouse from her early youth served as the model for the one depicted in the paintings, and we thus feel a bit transported back to her childhood. Yet even though dollhouses are now mostly associated with children, when they first emerged at the end of the Renaissance they were a pastime for adults, who collected and carefully decorated them with idealized interiors.

The dollhouse as we know it today—meaning, a young girls’ hobby—emerged in eighteenth-century Europe during the Industrial Revolution. One of the most famous historical dollhouses belonged to Queen Mary of England (1867–1953) and was designed by the well-known architect Sir Edwin Lutyens; the English writer Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the iconic Sherlock Holmes books, even wrote to-scale books to stock its library. Queen Mary’s dollhouse is still on view today at Windsor Castle, and is seen by millions of visitors every year. By far the most famous dollhouse in the world of art is the so-called Stettheimer Dollhouse, on view at the Museum of the City of New York, made by Carrie Stettheimer (1869–1944), sister of notable artist and art collector Florine Stettheimer. Carrie worked on the house from 1916 to 1935. Its art collection includes original miniature artworks by Alexander Archipenko, Gaston Lachaise, and Marcel Duchamp; Duchamp made for it a miniature copy of his famous painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1912). Likewise, Weyant’s painted scenes are often homages to or direct citations of artists she admires, or references to movies or literature she loves. Her painted dollhouse is in effect a gallery within the gallery, revealing influences that have shaped her as an artist.

Weyant spoke to me recently about her fascination with the literary character Eloise, created by Kay Thompson and illustrated by Hilary Knight in the 1950s. Eloise is a young girl who lives on the top floor of the Plaza Hotel on New York’s Fifth Avenue together with her absent-minded nanny, her dog Weenie, and a turtle named Skipperdee. Eloise is an independent young girl up to all sorts of mischief, for instance roller-skating down the corridors of the Plaza, pouring champagne down the mail chute, or writing her name on the hotel walls. The book’s subtitle, “A Book for Precocious Grown-Ups,” sums up Weyant’s interest in the story—it is in fact a book for those in between childhood and adulthood.

Titles play an important part in Weyant’s work. A painting of a sad-looking doll with Kleenex tissues in her bra to make her breasts appear bigger is titled Some Dolls are Bigger Than Others, a reference to the famous Smiths song “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others” (1985). Another, showing one of the dolls escaping the house via a rope such that we only see the feet through the window, perhaps alludes to the teenager’s suicide scene in Luchino Visconti’s well-known but heavily criticized film The Damned(1969), which takes place inside a mostly empty mansion. Weyant titled this work Escape Artist—I imagine Visconti himself here, fleeing the critics who panned his movie. One particularly clever work is John, Weyant’s version of John Currin’s Anna (2004), showing a woman’s face half-obscured by a candelabra. In Weyant’s painting a girl playing cards is equally obscured by an almost identical candleholder. Cards are a recurring motif in Weyant’s work, and relate not only to games like poker, solitaire, and rummy but also to card tricks, positing the artist as a trickster who plays games with her audience. This is very clear in her painting Self Portrait of a Gambler, showing four playing cards that spell out Weyant’s first name, Anna (aces for the two As and 2 cards turned sideways for the Ns). The work effectively functions as the artist’s signature for the overall installation, but it also speaks to the fact that this is Weyant’s first solo exhibition, in which she, figuratively speaking, is putting her cards on the table. Another painting involving cards might be related to Balthus’s The Card Game (1950).

Weyant has titled her painting From A to A, and we see in it only the leg and foot of a girl hiding an ace of diamonds under a table. From A to A plays with the concept of “From A to B” or “From A to Z.” Here, however, there is no start or finish line, no clear parameters, neither beginning nor end, no particular alphabet to follow. There is simply no place to go. Everyone is trapped in its hermetic, dreamlike scenario.

Other paintings continue Weyant’s exploration of art history without being too direct or obvious. There is for example Put Yourself in My Shoes, in which we see an empty bed with two legs sticking out underneath and a pair of black shoes nearby. Francesca Woodman’s photographs come to mind. Tales of a Tub references another painting, this time a historical one: Vermeer’s famous Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Widow (ca. 1657–59). Vermeer’s work made the news when it was revealed that there is a second character in the room (whom someone else painted over after his death), which if visible would give the painting a vastly different meaning. The idea of a hidden ghost in a work is very much in line with Weyant’s interest in the surreal, the world of dreams, and the uncanny. Weyant also looks to art with biblical content from the baroque era. The doll in Lance in Her Side has had her appendix removed, resulting in a small scar on her torso, which evokes the five stigmata of Christ crucified: the nails through hands and feet, the scars from whipping, and a wound from the lance of a Roman legionnaire. The most obvious example of a painting about the five holy wounds is Diego Velázquez’s Christ on the Cross (1632). Simultaneously the appendix scar points, perhaps more recognizably, to the 1939 book Madeline by Ludwig Bemelmans.

Despite all the references, one might say that with this initial solo exhibition of her work, her first public offering, Weyant is exorcising the ghosts of her artistic past—the artists, writers, and filmmakers who have shaped her sense of culture and the world. Now, we imagine, after this first show, she can move forward with more freedom, having outlined her particular conversation with art history. In our conversation about her show, Weyant also mentioned Michael Haneke’s film The White Ribbon (2009), in which a group of children terrorize a German village just before the outbreak of World War II, and Charlotte, Scarlett Johansson’s character in Sofia Coppola’s film Lost in Translation (2003). Coppola has made it a bit of a motif to use female characters who are mature for their age, even a bit wicked. Weyant also mentions the malicious but seemingly innocent Amma Crellin in the HBO miniseries Sharp Objects (2018) (based on the 2006 book by Gillian Flynn), who also plays with a dollhouse. Weyant is fascinated by adolescent girls who on the surface seem innocent but could stab someone at any moment.

One other artist and director who comes to mind in this context is Larry Clark, whose 1995 movie Kids (based on a screenplay by Harmony Korine, who would later also direct Spring Breakers [2013] about a group of adolescent girls on spring break who become involved with criminal activities) is perhaps the definitive work of hedonistic adolescent behavior in regard to drugs, sex, and general unruliness. Yet it is not so much the (male-initiated) rowdiness and outward abrasiveness of Kids that Weyant is interested in. Her work is more devious and haunting, with a poetic undertone somewhere nearer the German Romantic painters of the early eighteenth century. The transgressions are subtle, under a veneer of presumed innocence—including her own.

The paintings have very distinct color range dominated by various shades of dark green, including the beautiful Scalamandre (one of the world’s most prestigious fabric and wall covering manufacturers) inspired wallpaper. While visiting her studio I noticed a photograph from 2004 of her elementary school class in Calgary, with all the students wearing the same dark-green uniform. Weyant confirmed that there is a strong connection between her use of the color green in her paintings, particularly multiple dark shades of green, and the greens of her adolescence, which in the case of the admittedly ugly outfit manifested in rebelliousness. The theme of childhood purity corrupted by violence (sometime by adults, sometimes otherwise) is heavily present in Weyant’s work. It moves like a twisted fairy tale, threatening truth and forming a clear iconography of much less innocent future. Welcome to the Dollhouse tells a story of adolescent torment that reverberates into adulthood. The works hint at a pervading, true-to-life wickedness hidden beneath distracting veneers.